When media outlets reported that Sealed Air, the company that makes bubble wrap, was creating a new, un-poppable type of bubble wrap, the world reacted with horror and outrage. As one writer for Vice put it, “Sealed Air’s new Bubble Wrap apparently answers the wants and needs of shipping companies, but what about our needs?” Critical consensus seemed to be that popping bubble wrap is a time-honored pastime that is fun for all ages. In this article, we take a closer look at the science behind this popular product.

Kathleen Dillon’s hypothesis

Believe it or not, a bit of actual scientific research has gone into answer this question. In the early 1990s, psychology professor Kathleen M. Dillon asked a group of undergraduates to pop some bubble sheets, while a control group abstained. Those who got to pop two sheets of Bubble Wrap felt at once calmer and more awake after they were done than before they’d started; they also reported higher levels of calmness and alertness than the control group.

In her study report, Dillon explained her hypothesis on why this might be. “It has to do with a very natural, human response to stress: freezing in your tracks. In real danger, this might be helpful, because it gives you a moment to decide what to action to take—better to fight back, or flee? A similar thing might happen when people are nervous or stressed, and so it could be that little nervous motions like finger tapping or foot jiggling—or Bubble Wrap popping!—are ways of releasing that muscle tension, which helps reduce the feeling of stress.

Dillon went on to defend her thesis by quoting a 1970s book about the calming powers of touch: “In ancient Greece it was customary, and is still in so much of Asia, to carry a smooth-surfaced stone, or amber, or jade, sometimes called a ‘fingering piece.’ Such a ‘worrybead,’ as it is also named, by its pleasant feel, serves to produce a calming effect. The telling of beads by religious Catholics seems to produce a similar result.” This is why, she concludes, humans may consider it relaxing to keep their hands busy with little projects like needlework.

Other possible factors

Dillon is not the only scientist or psychiatrist to examine the addictive, pleasing nature of bubble popping. Others have proposed additional reasons why humans like to pop things, including:

- Release of pressure. Popping a bubble is essentially creating a moment of intense stress, followed by a release. The release of any type of pressure causes our brains to produce feel-good chemicals, like dopamine and norepinephrine.

- Meditative repetition. Performing the same actions repeatedly can lull your brain into a meditative state. In other words, popping bubble wrap can have the same effect as lifting weights, chanting a phrase or syllable over and over, or drawing a repetitive pattern.

- Immediate gratification. Most of us spend a great deal of time waiting for good things to happen—for lunch time to come; for packages to arrive; for paychecks to be processed. But popping a bubble gives us an instantaneous, albeit tiny, sense of accomplishment.

- Sensory stimulation. You may have heard of the term ASMR, or Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response.” This refers to a “tingly” feeling that some experience in response to certain sounds or feelings. Both the noise that popping bubble wrap makes, and the sensation of air tickling the fingers, might cause an ASMR reaction.

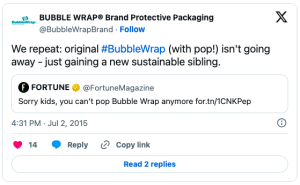

Don’t worry—you don’t need to stop the pop

If you’re worried that the bubble wrap of the future will rob you of all that wonderful dopamine, don’t be. Following an outpouring of concern, Sealed Air reassured consumers that the original bubble wrap the company has made for over 60 years will still be available to consumers.

Its newer, unpoppable product, iBubble Wrap, is simply an addition to the Bubble Wrap product family—hopefully, one that will be more reusable, sustainable, and cost-efficient. But if you just can’t resist that popping catharsis, don’t worry. A wide variety of Sealed Air products will continue to be available wherever you get your packing materials.